Lore, Language, Land and Legacy

How Scotland's Ancient Tongues and Tales Offer a Blueprint for Understanding Land and Weather

Wild geese, wild geese ganging t’ the sea

Good weather it will be

Wild geese, wild geese ganging t’ the hill

The weather it will spill.

In Moray, where the Spey runs high after summer drought and the sky hangs low in the time of the small sun, this old weather rhyme is more than just a saying. It is part of the way we read the sky. When the evenings draw in and the skeins of geese darken the air with their honking, we are not just watching birds on the move; we are reading a kind of living text, written in wings and weather.

My dad always swore that when you saw an unusually large number of geese on the wing, it meant the weather was changing. That, too, is lore, not data in a spreadsheet, but knowledge carried in a family, in a place, in a language. Between the foothills of the Cairngorms and the Moray Firth lies the Laigh o’ Moray, a strip of fertile land where we grow the barley that fuels Speyside whisky production. The geese and their rhyme are only one strand in the web of stories, sayings and place‑names that tie people here to land and weather.

Connections

I come from a long line of smallholders, crofters and farm labourers. The land is important to me; it is in my blood. I went on to study zoology at university, choosing ecology and animal behaviour whenever I could. I wanted to understand not only animals, but their relationships with each other and with the places they live.

If you follow me on Substack, you will know that I am the co‑founder of SpookyScotland.net. The site digs into the history behind hauntings, Scotland’s deliciously dark past, and the rich seam of Scottish folklore and mythology. I am also a primary school teacher currently taking a career break to follow some long‑held dreams. This year has been filled with making sourdough bread, expanding our website and writing my debut novel, The Carlin’s Eye, a historical fantasy set in Pictland in the north of what would later become Scotland.

I am also learning Gaelic, and I speak Doric Scots. Both are slowly changing how I look at the land around me. They give me different ways to name a hill, a wind, a bird. They tune my ear to patterns I might otherwise miss. This year has been full of those moments of connection, as if the landscape were offering back a set of forgotten instructions on how to belong.

One of the most striking moments came when I was writing a web post about the Caledonian Forest. I came across research arguing that there is a correlation between the loss of Scottish folklore and the rate of loss of the Caledonian Forest, the natural woodland which covered much of Scotland after the Ice Age. You can see this on the ground where I live. In Moray there are no surviving strands of Caledonian Forest and no major collected works of local mythology or folktales. In Badenoch and Strathspey, by contrast, you find both: substantial remnants of ancient woodland and several collections of folktales.

It is as though the stories and the trees have withered together.

Folklore tales are not just quaint entertainment; they are ecological blueprints for the communities we live in. They carry instructions about when certain storms and winds occur at given times of the year.

You can see this in the great seasonal drama between the Cailleach, the goddess of winter, and Bride, the goddess of summer. In one thread of the story, the Cailleach holds Bride captive until the coming of Angus Og, the bright young god of youth and Summer. As the Cailleach chases the lovers across the land, she shapes the season. Her rage sends sudden storms that break what seemed like a gentle spell of spring. Her weariness brings still, bright days. In some versions, her final act of throwing down her staff marks the last blast of winter before she turns to stone or sleep. For people who lived close to the land, this was not just a romantic tale. It explained why spring is changeable, why certain winds and storms come when they do, and it gave a pattern to a season that can otherwise feel confusing and cruel.

When those tales are weakened or lost, those blueprints fade.

Language, loss and power

When a language is suppressed, its lore begins to disappear. Scots and Gaelic have both been actively discouraged and marginalised in the past. These are the tongues of working people, farmers, crofters, fishermen, labourers, the people whose livelihoods depended most directly on understanding land and sea. They are the languages in which stories were told, folk songs and ballads were sung, and weather rhymes were remembered by heart around the fire.

Their suppression is not an accident of history. It belongs to the same colonial mindset that British elites carried into Wales and Ireland and then exported across the wider world. Devaluing local languages has long been a way of devaluing local knowledge and asserting control.

In the fifteenth century, the picture was very different. Around 1450, Scots was officially recognised as the language of the Scottish state. Our laws were written in Scots, and it served as a language of government and literature in its own right, not a rough version of anything else. Today, the European Commission for Regional or Minority Languages recognises Scots as a minority language, acknowledging its distinct status and its vulnerability.

More recently, there has been a move to repair some of the damage. In 2025, the Scottish Parliament passed the Scottish Languages Act, which made Scots an official language of Scotland alongside Scottish Gaelic and introduced educational standards and support for both. It is a significant step towards treating these tongues not as curiosities, but as living languages with a future in schools, public life and cultural creation.

For a long time, though, English was the unquestioned language of education and academia. Children were made to feel inferior if they spoke Scots or Gaelic in the Playground or classroom. Advancement often came at the price of leaving a language behind. If you spoke Scots, you were told that you were speaking a dialect of English, with the clear implication that it was broken, wrong, something to grow out of and be ashamed of.

Speaking between worlds: Doric and code‑switching

One of the fascinating things about Scots, is that many of us live on a linguistic continuum. We slide, often without noticing, between Scots English and Scots, adjusting our speech depending on who we are talking to and where we are.

Doric is the name commonly given to the North‑East variety of Scots, spoken in Aberdeenshire, parts of Moray, and along the Buchan and Banff coasts. It has its own rich vocabulary, pronunciation and idioms, shaped by farming, fishing and centuries of local life. If you have ever heard someone say “fit like?” for “how are you?”, or “quine” and “loon” for “girl” and “boy”, you have heard Doric. I notice this in myself. If I am talking to someone from Aberdeenshire, I tend to reply with a thicker accent and more Doric words than I might use with someone from Elgin.

Once a month I meet with a Gaelic group, and the native speakers talk about how they spoke Gaelic at home but had to switch to English at school. That act of switching, and the emotional charge it carries, runs right through our recent history. Gaelic‑medium education has been available for children in parts of the Highlands and Islands for some time now, giving new generations a chance to learn in their ancestral language.

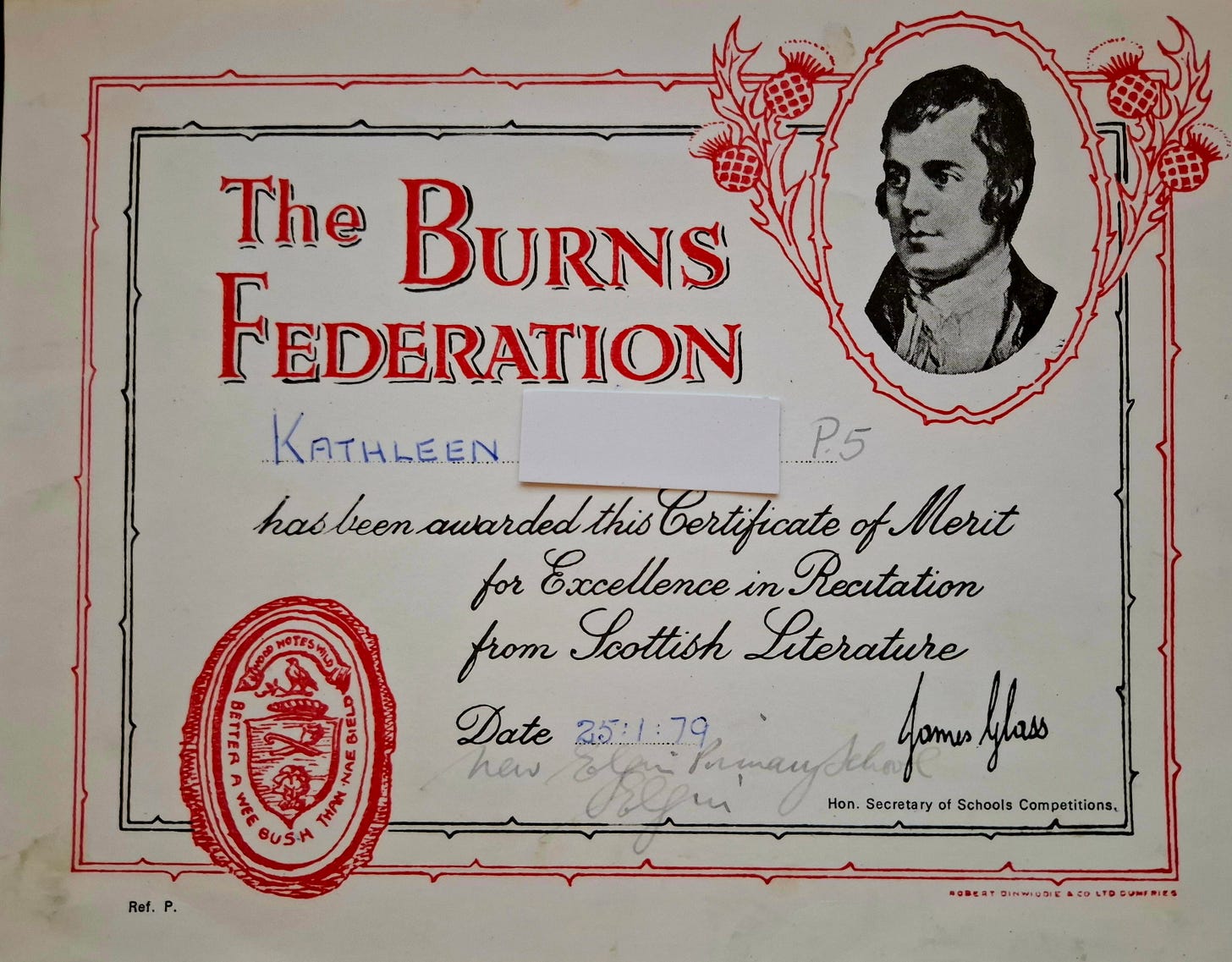

My own experience of Scots in school, by contrast, was confined to an annual competition to recite a Scots poem. I won it in Primary 5, a small but important validation that this language belonged in the classroom too.

I am deeply grateful to my mother, who wrote poetry in Doric and always encouraged me to feel proud of being a Doric speaker. That pride matters. Without it, a language shrinks to the edges of private life. With it, the language is strong enough to carry stories about land, weather and history.

Folklore for everyone, but mind your sources

Things are changing. There is a growing interest in Scottish folklore, myth and story. On the whole, this is a cause for celebration. More people are discovering kelpies and selkies, bean‑nighe and second sight. They are looking again at the landscapes these tales arose from.

But it is a double‑edged sword. Many people are writing about Scottish folklore and getting their information from unreliable sources online. Perhaps they have been on a tour where the guide embellished a tale or blurred two stories together. Then they go home and share it as fact. Over time, details get smudged, place‑names detach from their places, and genuinely old traditions are quietly replaced by recent inventions.

Folklore is for everyone. You do not need a degree or a family tree in the Highlands to love these stories. But if you care about them, and about the lands they belong to, then it is worth being careful. Check your sources. Look for primary collections, fieldwork, and accounts recorded as close as possible to the communities they came from. Pay attention to who is speaking, in what language, and from which place.

Above all, always connect the tales back to the land. A kelpie without its loch is just a monster. A geese rhyme without its migration route and weather pattern is just a jingle. When we reconnect folklore with landscape, language and ecology, we do more than preserve old stories. We rebuild the blueprints that once helped people to have more sustainable relationships with the natural world.